Synthetic Data & Distillation

Reinforcement learning from human feedback is deeply rooted in the idea of keeping a human influence on the models we are building. When the first models were trained successfully with RLHF, human data was the only viable way to improve the models in this way.

Humans were the only way to create high enough quality responses to questions for training. Humans were the only way to collect reliable and specific feedback data to train reward models.

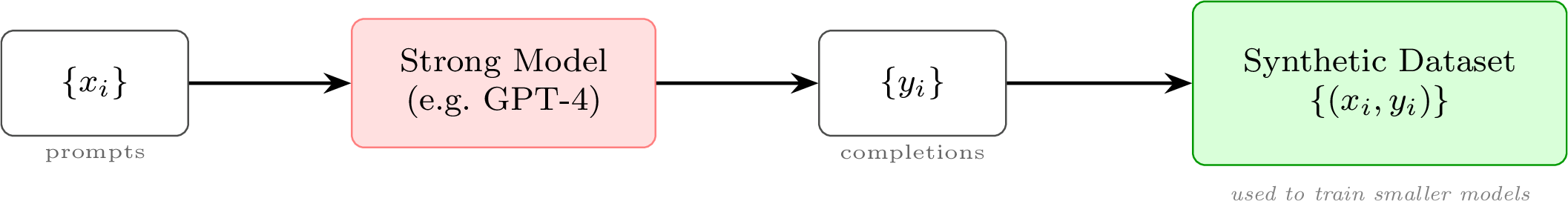

As AI models got better, this assumption rapidly broke down. The possibility of synthetic data, which is far cheaper and easier to iterate on, enabled the proliferation from RLHF being the center of attention to the idea of a broader “post-training” shaping the models. This chapter provides a cursory overview of how and why synthetic data is replacing or expanding many pieces of the RLHF pipeline.

One common criticism of synthetic data is model collapse – the idea that repeatedly training on a model’s own generations can progressively narrow the effective training distribution [1]. As diversity drops, rare facts and styles are underrepresented, and small mistakes can be amplified across iterations, leading to worse generalization. In practice, these failures are most associated with self-training on unfiltered, repetitive, single-model outputs; mixing in real/human data, using diverse teachers, deduplication, and strong quality filters largely avoids the collapse regime. For today’s frontier training pipelines, evidence suggests synthetic data can, and should, be used at scale without the catastrophic regressions implied by the strongest versions of the collapse story [2] [3].

The leading models need synthetic data to reach the best performance. Synthetic data in modern post-training encompasses many pieces of training – language models are used to generate new training prompts from seed examples [4], modify existing prompts, generate completions to prompts [5], provide AI feedback to create preference data [6], filter completions [7], and much more. Synthetic data is key to post-training.

The ability for synthetic data to be impactful to this extent emerged with GPT-4 class models. With early language models, such as Llama 2 and GPT-3.5-Turbo, the models were not reliable enough in generating or supervising data pipelines. Within 1-2 years, language models were far superior to humans for generating answers. In the transition from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4 class models, the ability for models to perform LLM-as-a-judge tasks also emerged. GPT-4 or better models are far more robust and consistent in generating feedback or scores with respect to a piece of content.

Through the years since ChatGPT’s release at the end of 2022, we’ve seen numerous, impactful synthetic datasets – some include: UltraFeedback [6], the first prominent synthetic preference dataset that kickstarted the DPO revolution, or Stanford Alpaca, one of the first chat-style fine-tuning datasets, in 2023, skill-focused (e.g. math, code, instruction-following) synthetic datasets in Tülu 3 [8], or OpenThoughts 3 and many other synthetic reasoning datasets in 2025 for training thinking models [9]. Most of the canonical references for getting started with industry-grade post-training today involve datasets like Tülu 3 or OpenThoughts 3 above, where quickstart guides often start with smaller, simpler datasets like Alpaca due to far faster training.

A large change is also related to dataset size, where fine-tuning datasets have grown in the number of prompts, where Alpaca is 52K, OpenThoughts and Tülu 3 are 1M+ samples, and in the length of responses. Longer responses and more prompts results in the Alpaca dataset being on the order of 10M training tokens, where Tülu is 50X larger at about 500M, and OpenThoughts 3 is bigger still at the order of 10B tokens.

Throughout this transition, synthetic data has not replaced human data uniformly across the pipeline. For instruction data (SFT), synthetic generation has largely won —- distillation from stronger models now produces higher quality completions than most human writers can provide at scale (with some exception in the hardest, frontier reasoning problems). For preference data in RLHF, the picture is more mixed: academic work shows synthetic preference data performs comparably, yet frontier labs still treat human preference data as a competitive moat. For evaluation, the split takes a different flavor: LLM-as-a-judge scales the scoring of model outputs cost-effectively, but the underlying benchmarks and ground-truth labels still require human creation. The pattern is that synthetic data dominates where models exceed human reliability, while humans remain essential at capability frontiers, for establishing ground truth, and for guiding training.

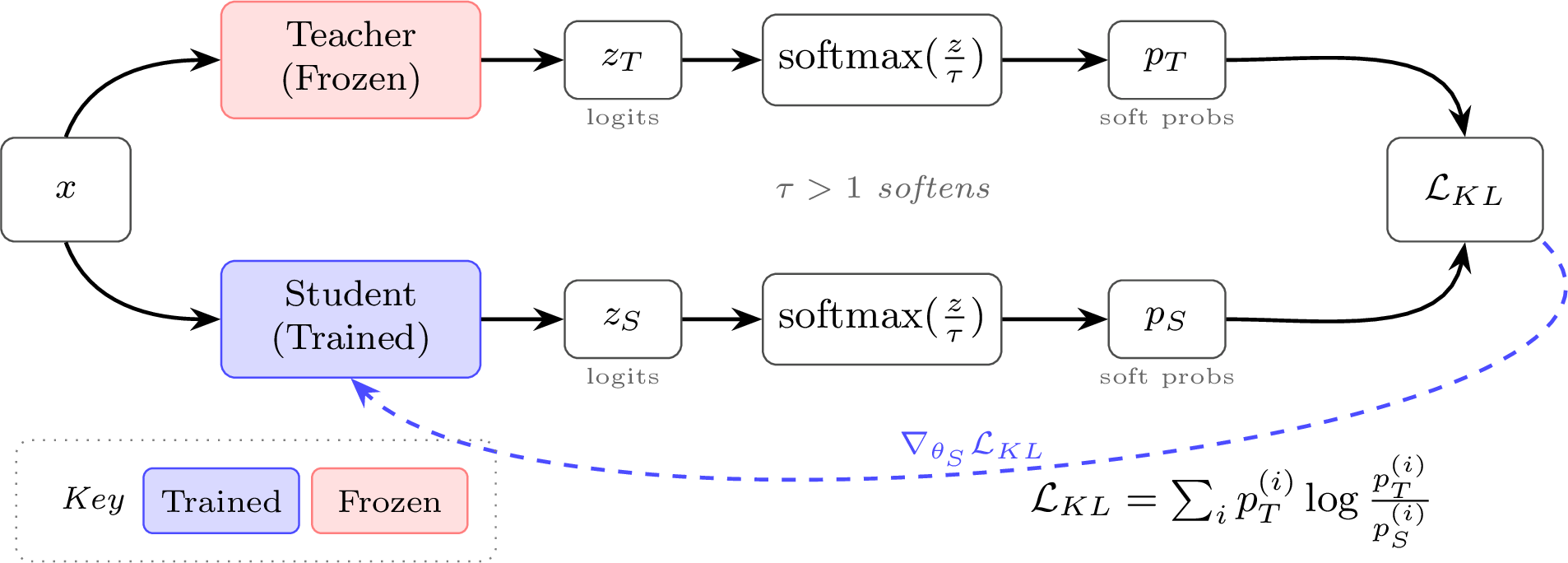

The term distillation has been the most powerful form of discussion around the role of synthetic data in language models. Distillation as a term comes from a technical definition of teacher-student knowledge distillation from the deep learning literature [10].

Distillation colloquially refers to using the outputs from a stronger model to train a smaller model.

In post-training, this general notion of distillation takes two common

forms:

In post-training, this general notion of distillation takes two common

forms:

- As a data engine to use across wide swaths of the post-training process: Completions for instructions, preference data (or Constitutional AI), or verification for RL.

- To transfer specific skills from a stronger model to a weaker model, which is often done for specific skills such as mathematical reasoning or coding.

The first strategy has grown in popularity as language models evolved to be more reliable than humans at writing answers to a variety of tasks. GPT-4 class models expanded the scope of this to use distillation of stronger models for complex tasks such as math and code (as mentioned above). Here, distillation motivates having a model suite where often a laboratory will train a large internal model, such as Claude Opus or Gemini Ultra, which is not released publicly and just used internally to make stronger models. With open models, common practice is to distill training data from closed API models into smaller, openly available weights [11]. Within this, curating high-quality prompts and filtering responses from the teacher model is crucial to maximize performance.

Transferring specific skills into smaller language models uses the same principles of distillation – get the best data possible for training. Here, many papers have studied using limited datasets from stronger models to improve alignment [12], mathematical reasoning [13] [14], and test-time scaling [15]. # Constitutional AI & AI Feedback

Soon after the explosion of growth in RLHF, RL from AI Feedback (RLAIF) emerged as an alternative approach where AIs could approximate the human data piece of the pipeline and accelerate experimentation or progress. AI feedback, generally, is a larger set of techniques for using AI to augment or generate data explaining the quality of a certain input (which can be used in different training approaches or evaluations), which started with pairwise preferences [16] [17] [18]. There are many motivations to using RLAIF to either entirely replace human feedback or augment it. Within the RLHF process, AI feedback is known most for its role within the preference data collection and the related reward model training phase (of which constitutional AI is a certain type of implementation). In this chapter, we focus on the general AI feedback and this specific way of using it in the RLHF training pipeline, and we cover more ways of understanding or using synthetic data later in this book.

As AI feedback matured, its applications expanded beyond simply replacing human preference labels. The same LLM-as-a-judge infrastructure that enabled cheaper preference data collection also enabled scalable evaluation (see Chapter 16), and more recently, rubric-based rewards that extend RL training to domains without verifiable answers – a frontier explored later in this chapter.

Balancing AI and Human Feedback Data

AI models are far cheaper than humans at generating a specific quantity of feedback, with a single piece of human preference data costing as of writing this on the order of $1 or higher (or even above $10 per prompt), AI feedback with a frontier AI model, such as GPT-4o costs less than $0.01. Beyond this, the cost of human labor is remaining roughly constant, while the performance of leading models at these tasks continues to increase while price-per-performance decreases. This cost difference opens the market of experimentation with RLHF methods to an entire population of people previously priced out.

Other than price, AI feedback introduces different tradeoffs on performance than human feedback, which are still being investigated in the broader literature. AI feedback is far more predominant in its role in evaluation of the language models that we are training, as its low price lets it be used across a variety of large-scale tasks where the cost (or time delay) in human data would be impractical. All of these topics are deeply intertwined – AI feedback data will never fully replace human data, even for evaluation, and the quantity of AI feedback for evaluation will far outperform training because far more people are evaluating than training models.

The exact domains and applications – i.e. chat, safety, reasoning, mathematics, etc. – where AI feedback data outperforms human data is not completely established. Some early work in RLAIF shows that AI feedback can completely replace human data, touting it as an effective replacement [16] and especially when evaluated solely on chat tasks [6] [19]. Early literature studying RLHF after ChatGPT had narrow evaluation suites focused on the “alignment” of models that act as helpful assistants across a variety of domains (discussed further in Chapter 17). Later work takes a more nuanced picture, where the optimal equilibrium on a broader evaluation set, e.g. including some reasoning tasks, involves routing a set of challenging data-points to accurately label to humans, while most of the data is sent for AI feedback [20] [21]. While there are not focused studies on the balance between human and AI feedback data for RLHF across broader domains, there are many technical reports that show RLHF generally can improve these broad suite of evaluations, some that use DPO, such as Ai2’s Tülu 3 [8] & Olmo 3 [22], or HuggingFace’s SmolLM 3 [23], and others that use online RLHF pipelines, such as Nvidia’s work that uses a mix of human preference data from Scale AI and LLM-based feedback (through the helpsteer line of work [24] [25] [26] [27]): Nemotron Nano 3 [28], Nemotron-Cascade [29], or Llama-Nemotron reasoning models [30].

Overall, where AI feedback and related methods are obviously extremely useful to the field, it is clear that human data has not been completely replaced by these cheaper alternatives. Many hypotheses exist, but it is not studied if human data allows finer control of the models in real-world product settings or for newer training methods such as character training (an emerging set of techniques that allow you to precisely control the personality of a model, covered in Chapter 17). For those getting started, AI feedback should be the first attempt, but for pipelines that’re scaling to larger operations the eventual transition to include human feedback is likely.

The term RLAIF was introduced in Anthropic’s work Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback [31], which resulted in initial confusion in the AI community over the relationship between the two methods in the title of the paper (Constitutional AI and AI Feedback). Since the release of the Constitutional AI (CAI) paper and the formalization of RLAIF, RLAIF has become a default method within the post-training and RLHF literatures – there are far more examples than one can easily enumerate. The relationship should be understood as CAI was the example that kickstarted the broader field of RLAIF.

A rule of thumb for the difference between human data and AI feedback data is as follows:

- Human data is high-noise and low-bias. This means that collection and filtering of the data can be harder, but when wrangled it’ll provide a very reliable signal.

- Synthetic preference data is low-noise and high-bias. This means that AI feedback data will be easier to start with, but can have tricky, unintended second-order effects on the model that are systematically represented in the data.

This book highlights many academic results showing how one can substitute AI preference data in RLHF workflows and achieve strong evaluation scores [20], but broader industry trends show how the literature of RLHF is separated from more opaque, best practices. Across industry, human data is often seen as a substantial moat and a major technical advantage.

Constitutional AI

The method of Constitutional AI (CAI), which Anthropic uses in their Claude models, is the earliest documented, large-scale use of synthetic data for RLHF training. Constitutional AI involves generating synthetic data in two ways:

- Critiques of instruction-tuned data to follow a set of principles like “Is the answer encouraging violence” or “Is the answer truthful.” When the model generates answers to questions, it checks the answer against the list of principles in the constitution, refining the answer over time. Then, the model is fine-tuned on this resulting dataset.

- Generates pairwise preference data by using a language model to answer which completion was better, given the context of a random principle from the constitution (similar to research for principle-guided reward models [32]). Then, RLHF proceeds as normal with synthetic data, hence the RLAIF name.

Largely, CAI is known for the second half above, the preference data, but the methods introduced for instruction data are used in general data filtering and synthetic data generation methods across post-training.

CAI can be formalized as follows.

By employing a human-written set of principles, which they term a constitution, Bai et al. 2022 use a separate LLM to generate artificial preference and instruction data used for fine-tuning [31]. A constitution \(\mathcal{C}\) is a set of written principles indicating specific aspects to focus on during a critique phase. The instruction data is curated by repeatedly sampling a principle \(c_i \in \mathcal{C}\) and asking the model to revise its latest output \(y^i\) to the prompt \(x\) to align with \(c_i\). This yields a series of instruction variants \(\{y^0, y^1, \cdots, y^n\}\) from the principles \(\{c_{0}, c_{1}, \cdots, c_{n-1}\}\) used for critique. The final data point is the prompt \(x\) together with the final completion \(y^n\), for some \(n\).

The preference data is constructed in a similar, yet simpler way by

using a subset of principles from \(\mathcal{C}\) as context for a feedback

model. The feedback model is presented with a prompt \(x\), a set of principles \(\{c_0, \cdots, c_n\}\), and two

completions \(y_0\) and \(y_1\) labeled as answers (A) and (B) from

a previous RLHF dataset. The new datapoint is generated by having a

language model select which output (A) or (B) is both higher quality

and more aligned with the stated principle. In earlier models this

could be done by prompting the model with The answer is:,

and then looking at which logit (A or B) had a higher probability, but

more commonly is now handled by a model that’ll explain its reasoning

and then select an answer – commonly referred to as a type of

generative reward model [33].

Specific LLMs for Judgement

As RLAIF methods have become more prevalent, many have wondered if we should be using the same models for generating responses as those for generating critiques or ratings. Specifically, the calibration of the LLM-as-a-judge used has come into question. Several works have shown that LLMs are inconsistent evaluators [34] and prefer their own responses over responses from other models (coined self-preference bias) [35].

As a result of these biases, many have asked: Would a solution be to train a separate model just for this labeling task? Multiple models have been released with the goal of substituting for frontier models as a data labeling tool, such as critic models Shepherd [36] and CriticLLM [37] or models for evaluating response performance akin to Auto-J [38], Prometheus [39], Prometheus 2 [40], or Prometheus-Vision [41] but they are not widely adopted in documented training recipes. Some find scaling inference via repeated sampling [42] [43] [44], self-refinement [45], or tournament ranking [46] provides a better estimate of the true judgement or higher-quality preference pairs. Other calibration techniques co-evolve the generation and judgement capabilities of the model [47]. It is accepted that while biases exist, the leading language models are trained extensively for this task – as its needed for both internal operations at AI labs and is used extensively by customers – so it is generally not needed to train your own judge, unless your task involves substantial private information that is not exposed on the public internet.

Rubrics: AI Feedback for Training

AI feedback’s role in training grew in late 2024 and intro 2025 as the field looked for avenues to scale reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (see Chapter 7). The idea of rubrics emerged as a way to get nearly-verifiable criteria for prompts that do not have clearly verifiable answers. This would allow a model to try to generate multiple answers to a problem and update (with RL) towards the best answers. This idea is closely related to other methods discussed in this chapter, and likely began functioning as the LLM judges and synthetic data practices improved across the industry. Now, RL with rubrics as rewards is established in providing meaningful improvements across skills such as scientific reasoning or factuality [48], [49], [50], [51].

An example rubric is shown below with its associated prompt [51]:

**Prompt**: As a museum curator, can you suggest five obscure artifacts that would be perfect for a "Mysteries of the Ancient World" exhibit? Each artifact should come from a different culture and time period, with a brief description of their historical significance and mysterious origins. These artifacts should leave visitors wondering about the secrets and lost knowledge of our past. Thank you for your expertise in bringing this exhibit to life.

** Rubric**:

1. The response includes exactly five distinct artifacts as requested. [Hard Rule]

2. The response ensures each artifact originates from a different culture and time period. [Hard Rule]

3. The response provides a brief description of each artifact's historical significance. [Hard Rule]

4. The response provides a brief description of each artifact's mysterious origins or unexplained aspects. [Hard Rule]

5. The response conveys a sense of intrigue and mystery that aligns with the theme of the exhibit. [Hard Rule]

6. The response clearly and accurately communicates information in a well-organized and coherent manner. [Principle]

7. The response demonstrates precision and clarity by avoiding unnecessary or irrelevant details. [Principle]

8. The response uses informative and engaging language that stimulates curiosity and critical thinking. [Principle]

9. The response shows thoughtful selection by ensuring each example contributes uniquely to the overall theme without redundancy. [Principle]

10. The response maintains consistency in style and format to enhance readability and comprehension. [Principle]The [Hard Rule] and [Principle] are

specific tags to denote the priority of a certain piece of feedback.

Other methods of indicating importance can be used, such as simple

priority numbers.

Rubric generation is generally done per-prompt in the training data, which accumulates meaningful synthetic data costs in preparation. To alleviate this, a general rubric is often applied as a starting point per-domain, and then the fine-grained rubric scores per-prompt are assigned by a supervising language model to guide the feedback for training. An example prompt to generate a rubric for a science task is shown below [48]:

You are an expert rubric writer for science questions in the domains of Biology, Physics, and Chemistry.

Your job is to generate a self-contained set of evaluation criteria ("rubrics") for judging how good a response is to a given question in one of these domains.

Rubrics can cover aspects such as factual correctness, depth of reasoning, clarity, completeness, style, helpfulness, and common pitfalls.

Each rubric item must be fully self-contained so that non-expert readers need not consult

any external information.

Inputs:

- question: The full question text.

- reference_answer: The ideal answer, including any key facts or explanations.

Total items:

- Choose 7-20 rubric items based on question complexity.

Each rubric item must include exactly three keys:

1. title (2-4 words)

2. description: One sentence beginning with its category prefix, explicitly stating what to look for.

For example:

- Essential Criteria: States that in the described closed system, the total mechanical energy (kinetic plus potential)

before the event equals the total mechanical energy after the event.

- Important Criteria: Breaks down numerical energy values for each stage, demonstrating that initial kinetic

energy plus initial potential energy equals final kinetic energy plus final potential energy.

- Optional Criteria: Provides a concrete example, such as a pendulum converting between kinetic and potential

energy, to illustrate how energy shifts within the system.

- Pitfall Criteria: Does not mention that frictional or air-resistance losses are assumed negligible when applying

conservation of mechanical energy.

3. weight: For Essential/Important/Optional, use 1-5 (5 = most important); for Pitfall, use -1 or -2.

Category guidance:

- Essential: Critical facts or safety checks; omission invalidates the response.

- Important: Key reasoning or completeness; strongly affects quality.

- Optional: Nice-to-have style or extra depth.

- Pitfall: Common mistakes or omissions; highlight things often missed.

Format notes:

- When referring to answer choices, explicitly say "Identifies (A)", "Identifies (B)", etc.

- If a clear conclusion is required (e.g. "The final answer is (B)"), include an Essential Criteria for it.

- If reasoning should precede the final answer, include an Important Criteria to that effect.

- If brevity is valued, include an Optional Criteria about conciseness.

Output: Provide a JSON array of rubric objects. Each object must contain exactly three keys-title, description, and weight.

Do not copy large blocks of the question or reference_answer into the text. Each description must begin with its category

prefix, and no extra keys are allowed.

Now, given the question and reference_answer, generate the rubric as described.

The reference answer is an ideal response but not necessarily exhaustive; use it only as guidance.Another, simpler example follows as [50]:

SYSTEM:

You generate evaluation rubrics for grading an assistant's response to a user prompt.

Rubric design rules:

- Each criterion must be atomic (one thing), objective as possible, and written so a grader can apply it consistently.

- Avoid redundant/overlapping criteria; prefer criteria that partition different failure modes.

- Make criteria self-contained (don't rely on unstated context).

- Include an importance weight for each criterion.

Output format (JSON only):

{

"initial_reasoning": "<brief rationale for what matters for this prompt>",

"rubrics": [

{

"reasoning": "<why this criterion matters>",

"criterion": "<clear, testable criterion>",

"weight": <integer 1-10>

},

...

]

}

USER:

User prompt:

{prompt}

Generate the rubric JSON now.As you can see, the prompts can be very detailed and are tuned to the training setup.

Rubrics with RL training are going to continue to evolve beyond their early applications to instruction following [52], deep research [53], evaluating deep research agents [54], or long-form generation [55].

Further Reading

There are many related research directions and extensions of Constitutional AI, but few of them have been documented as clear improvements in RLHF and post-training recipes. For now, they are included as further reading.

- OpenAI has released a Model Spec [56], which is a document stating the intended behavior for their models, and stated that they are exploring methods for alignment where the model references the document directly (which could be seen as a close peer to CAI). OpenAI has continued and trained their reasoning models such as o1 with a method called Deliberative Alignment [57] to align the model while referencing these safety or behavior policies.

- Anthropic has continued to use CAI in their model training, updating the constitution Claude uses [58] and experimenting with how population collectives converge on principles for models and how that changes model behavior when they create principles on their own and then share them with Anthropic to train the models [59].

- The open-source community has explored replications of CAI applied to open datasets [60] and for explorations into creating dialogue data between LMs [61].

- Other work has used principle-driven preferences or feedback with different optimization methods. [62] uses principles as context for the reward models, which was used to train the Dromedary models [32]. [63] uses principles to improve the accuracy of human judgments in the RLHF process. [64] train a reward model to generate its own principles at inference time, and use these to deliver a final score. [65] formulate principle-following as a mutual information maximization problem that the pretrained model can learn with no labels.