Tool Use & Function Calling

Language models using tools is a natural way to expand their capabilities, especially for high-precision tasks where external tools contain the information or for agents that need to interact with complex web systems. Tool-use is a skill that language models need to be trained to have, where RLHF and all the other methods presented in this book can refine it. Consider a question from a user such as:

User: Who is the president today?

A language model without tools will have a hard time answering this question due to the knowledge cutoff of pretraining data, but this is readily accessible information with one search query.

Before diving deeper, it is useful to distinguish related terms that are often used interchangeably:

- Tool use: the model emits a structured request (tool name and arguments); an orchestrator executes the tool; results are appended to the context; the model continues generating.

- Function calling: tool use where the arguments must conform to a declared schema for a set of functions (usually JSON Schema), enabling reliable parsing and validation.

- Code execution: a special case of tool use where the “tool” is a code interpreter (e.g., Python); results are returned as tool output.

An AI model uses any external tools by outputting special tokens to trigger a certain endpoint. These can be anything from highly specific tools, such as functions that return the weather at a specific place, to code interpreters or search engines that act as fundamental building blocks of complex behaviors. Our first example showcased where language models need more up-to-date information to complement the fixed nature of their weights trained on past data, but there are also tools such as code execution, which lets language models get around their probabilistic, generative nature and return precise answers. Consider the task of printing an approximation of pi to 50 digits (without reciting it from memory and risking hallucination). A language model with tools can do the following:

<code>

from decimal import Decimal, getcontext

getcontext().prec = 60

def compute_pi():

# Chudnovsky algorithm for computing pi

C = 426880 * Decimal(10005).sqrt()

K, M, X, L, S = 0, 1, 1, 13591409, Decimal(13591409)

for i in range(1, 100):

M = M * (K**3 - 16*K) // ((i)**3)

K += 12

L += 545140134

X *= -262537412640768000

S += Decimal(M * L) / X

return C / S

print(str(compute_pi())[:52])

</code>

<output>

3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937510

</output>This chapter provides an overview of the origins of tool-use in modern language models, its fundamentals and formatting, and current trade-offs in utilizing tools well in leading models.

The exact origin of the term “tool use” is not clear, but the origins of the idea far predate the post ChatGPT world where RLHF proliferated. Early examples circa 2015 attempted to build systems predating modern language models, such as Neural Programmer-Interpreters (NPI) [1], “a recurrent and compositional neural network that learns to represent and execute programs.” As language models became more popular, many subfields were using integrations with external capabilities to boost performance. To obtain information outside of just the weights many used retrieval augmented generation [2] or web browsing [3]. Soon after, others were exploring language models integrated with programs [4] or tools [5].

As the field matured, these models gained more complex abilities in addition to the vast improvements to the underlying language modeling. For example, ToolFormer could use “a calculator, a Q&A system, two different search engines, a translation system, and a calendar” [6]. Soon after, Gorilla was trained to use 1645 APIs (from PyTorch Hub, TensorFlow Hub v2, and HuggingFace) and its evaluation APIBench became a foundation of the popular Berkeley Function Calling Leaderboard [7]. Since these early models, the diversity of actions called has grown substantially.

Tool-use models are now deeply intertwined with regular language model interactions. Model Context Protocol (MCP) emerged as a common formatting used to connect language models to external data sources (or tools) [8]. With stronger models and better formats, tool-use language models are used in many situations, including productivity copilots within popular applications such as Microsoft Office or Google Workspace, scientific domains [9], medical domains [10], coding agents [11] such as Claude Code or Cursor, integrations with databases, and many other autonomous workflows.

Evaluating tool-use models involves multiple dimensions: exact-match metrics for tool name and argument correctness, schema validity, and end-to-end task completion in simulated environments. Reliability across trials also matters – \(\tau\)-bench introduced the pass^k metric (distinct from pass@k) to measure whether an agent succeeds consistently rather than occasionally [12]. ToolLLM and its ToolBench dataset provide a large-scale framework for training and evaluating tool use across 16,000+ real-world APIs [13], while the Berkeley Function Calling Leaderboard (BFCL) remains a popular benchmark for comparing models on function calling accuracy [7].

Interweaving Tool Calls in Generation

Function calling agents are presented data very similarly to other post-training stages. The addition is the content in the system prompt that instructs the model what tools it has available. An example formatted data point with the system prompt and tools available in JSON format is shown below:

<system>

You are a function-calling AI model. You are provided with function signatures within <functions></functions> XML tags. You may call one or more functions to assist with the user query. Don't make assumptions about what values to plug into functions.

</system>

<functions>

[

{

"name": "search_movies",

"description": "Search for movies by title and return matching results with IDs.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"query": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The search string for the movie title."

}

},

"required": ["query"]

}

},

{

"name": "get_movie_details",

"description": "Fetch detailed information about a movie including cast, runtime, and synopsis.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"movie_id": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The unique identifier for the movie."

}

},

"required": ["movie_id"]

}

},

{

"name": "get_showtimes",

"description": "Get movie showtimes for a given location and date.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"movie_id": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The unique identifier for the movie."

},

"zip_code": {

"type": "string",

"description": "ZIP code for theater location."

},

"date": {

"type": "string",

"description": "Date for showtimes in YYYY-MM-DD format."

}

},

"required": ["movie_id", "zip_code"]

}

}

]

</functions>

<user>

...

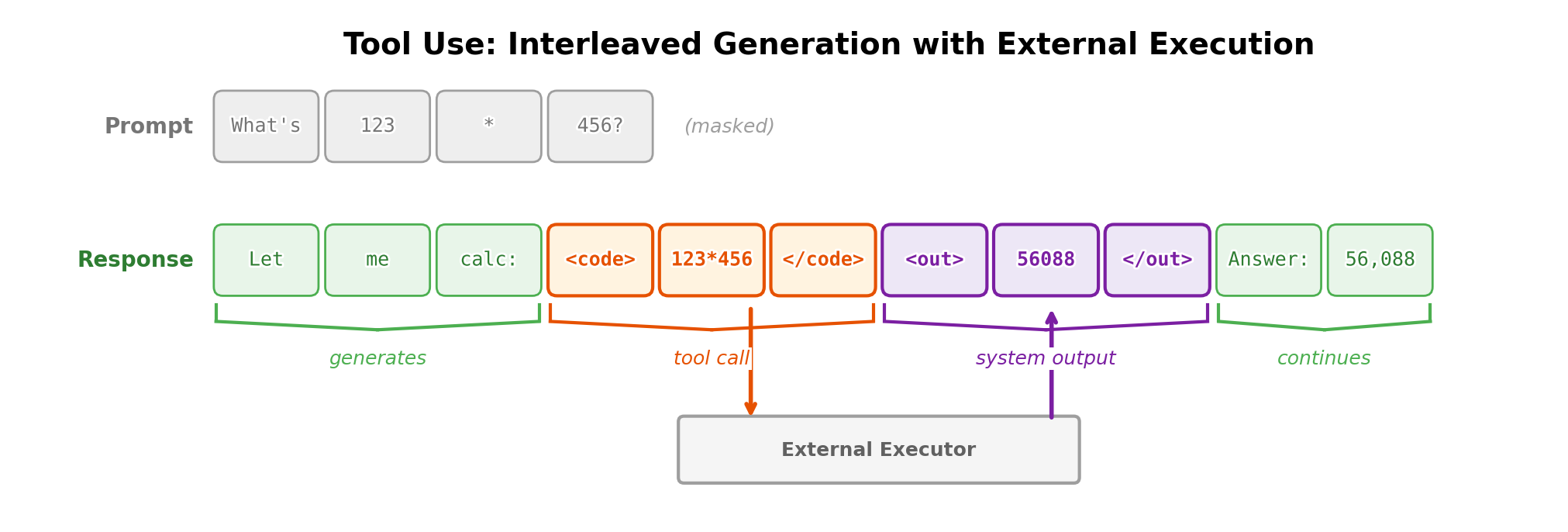

</user>While the language model is generating, if following the above

example, it would generate the tokens

search_movies("Star Wars") to search for Star Wars. This

is often encoded inside special formatting tokens, and then the next

tokens inserted into the sequence will contain the tool outputs. With

this, models can learn to accomplish more challenging tasks than many

simple standalone models.

A popular form of tool use is code-execution, allowing the model to get precise answers to complex logic or mathematics problems. For example, code-execution within a language model execution can occur during the thinking tokens of a reasoning model. As with function calling, there are tags first for the code to execute (generated by the model) and then a separate tag for output.

<|user|>

What is the 50th Fibonacci number? (Use the standard F_0=0, F_1=1 indexing.)</s>

<|assistant|>

<think>

Okay, I will compute the 50-th Fibonacci number with a simple loop, then return the result.

<code>

def fib(n):

a, b = 0, 1

for _ in range(n):

a, b = b, a + b

return a

fib(50)

</code>

<output>

12586269025

</output>

</think>

<answer>

The 50-th Fibonacci number is 12 586 269 025.

</answer>What is happening under the hood is the language model is interleaving tool inputs and outputs with standard autoregressively generated tokens. The orchestration loop that makes this possible looks something like:

messages = [...]

while True:

response = model(messages, tools=tools)

if not response.tool_calls:

return response.text

for call in response.tool_calls:

result = execute_tool(call.name, call.args)

messages.append({"role": "tool", "tool_call_id": call.id, "content": result})

Training for tool use is about getting the model to behave predictably with this different token flow—knowing when to emit a tool call, how to format arguments correctly, and how to incorporate results into its response. Open models must be trained to work with a variety of tools that users may connect off the shelf.

Multi-step Tool Reasoning

OpenAI’s o3 model represented a substantial step-change in how multi-step tool-use can be integrated with language models. This behavior is related to much earlier research trends in the community. For example, ReAct [14] showcased how actions and reasoning can be interleaved into one model generation:

In this paper, we explore the use of LLMs to generate both reasoning traces and task-specific actions in an interleaved manner, allowing for greater synergy between the two: reasoning traces help the model induce, track, and update action plans as well as handle exceptions, while actions allow it to interface with and gather additional information from external sources such as knowledge bases or environments.

With the solidification of tool-use capabilities and the take-off of reasoning models, multi-turn tool-use has grown into an exciting area of research [15].

Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open standard for connecting language models to external data sources and information systems [8]. At the data layer, MCP uses JSON-RPC 2.0 with discovery and execution methods for its primitives. Rather than requiring specific tool call formatting per external system, MCP enables models to access rich contextual information through a standardized protocol.

MCP is a simple addition on top of the tool-use content in this chapter – it is how applications pass context (data + actions) to language models in a predictable JSON schema. MCP servers that the models interact with have core primitives: resources (read-only data blobs), prompts (templated messages/workflows), and tools (functions the model can call). With this, the MCP architecture can be summarized as:

- MCP servers wrap a specific data source or capability.

- MCP clients (e.g., Claude Desktop, IDE plug-ins) aggregate one or more servers.

- Hosts, e.g. Claude or ChatGPT applications, provide the user/LLM interface; switching model vendors or back-end tools only means swapping the client in the middle.

MCP enables developers of tool-use models to use the same infrastructure to attach their servers or clients to different models, and at the same time models have a predictable format they can use to integrate external components. These together make for a far more predictable development environment for tool-use models in real-world domains.

An MCP server exposes tools to clients through a standardized JSON schema:

{

"name": "get_weather",

"description": "Get current weather for a location",

"inputSchema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "City name or coordinates"

}

},

"required": ["location"]

}

}A minimal Python MCP server implementing this tool:

from mcp.server import Server

from mcp.types import Tool, TextContent

server = Server("weather-server")

@server.list_tools()

async def list_tools():

return [Tool(

name="get_weather",

description="Get current weather",

inputSchema={

"type": "object",

"properties": {"location": {"type": "string"}},

"required": ["location"]

}

)]

@server.call_tool()

async def call_tool(name: str, arguments: dict):

if name == "get_weather":

weather = fetch_weather(arguments["location"])

return [TextContent(type="text", text=weather)]Implementation

There are multiple formatting and masking decisions when implementing a tool-use model:

- Python vs. JSON formatting: In this chapter, we included examples that format tool use as both JSON data-structures and Python code. Models tend to select one structure, different providers across the industry use different formats.

- Masking tool outputs: An important detail when training tool-use models is that the tokens in the tool output are masked from the model’s training loss. This ensures the model is not learning to predict the output of the system that it does not directly generate in use (similar to prompt masking for other post-training stages).

- Multi-turn formatting for tool invocations: It is common practice when implementing tool-calling models to add more structure to the dataloading format. Standard practice for post-training datasets is a list of messages alternating between user and assistant (and often a system message). The overall structure is the same for tool-use, but the turns of the model are split into subsections of content delimited by each tool call. An example is below.

messages = [

{

"content": "You are a function calling AI model. You are provided with function signatures within <functions></functions> XML tags. You may call one or more functions to assist with the user query. Don't make assumptions about what values to plug into functions.",

"function_calls": null,

"functions": "[{\"name\": \"live_giveaways_by_type\", \"description\": \"Retrieve live giveaways from the GamerPower API based on the specified type.\", \"parameters\": {\"type\": {\"description\": \"The type of giveaways to retrieve (e.g., game, loot, beta).\", \"type\": \"str\", \"default\": \"game\"}}}]",

"role": "system"

},

{

"content": "Where can I find live giveaways for beta access and games?",

"function_calls": null,

"functions": null,

"role": "user"

},

{

"content": null,

"function_calls": "live_giveaways_by_type(type='beta')\nlive_giveaways_by_type(type='game')",

"functions": null,

"role": "assistant"

}

]- Tokenization and message format details: Tool calls in OpenAI messages format often undergo tokenization through chat templates (the code for controlling format of messages sent to the model), converting structured JSON representations into raw token streams. This process varies across model architectures—some use special tokens to demarcate tool calls, while others maintain structured formatting within the token stream itself. Chat template playgrounds provides an interactive environment to explore how different models convert message formats to token streams.

- Reasoning token continuity: As reasoning models have emerged, with their separate token stream of “reasoning” before an answer, different implementations exist for how they’re handled with tool-use in the loop. Some models preserve reasoning tokens between tool-calling steps within a single turn, maintaining context across multiple tool invocations. However, these tokens are typically erased between turns to minimize serving cost (but aren’t always – this is a design decision).

- API formatting across providers (As of July

2025): Different providers use conceptually similar but technically

distinct formats. OpenAI uses

tool_callsarrays with unique IDs, Anthropic employs detailedinput_schemaspecifications with<thinking>tags, and Gemini offers function calling modes (AUTO/ANY/NONE). When using these models via an API, the tools available are defined in a JSON format and then the tool outputs in the model response are stored in a separate field from the standard “tokens generated.” For another example, the open-source vLLM inference codebase implements extensive parsing logic supporting multiple tool calling modes and model-specific parsers, providing insights into lower-level implementation considerations [16]. - Schema conformance and constrained decoding: Production systems often enforce valid JSON and correct argument types using constrained decoding or “strict mode” options, reducing retries from malformed outputs. Some closed model providers do additional post-training specifically to make structured JSON output reliable, where for open models this is handled as an inference flag in systems like VLLM.

- Tool output context consumption: Tool outputs can quickly consume the model’s context window, especially with search or retrieval tools that return many results. Systems must decide how to truncate, summarize, or paginate tool outputs to keep context manageable while preserving the information the model needs to continue.

Tying this back to post-training: where does tool-use training data come from, and what objectives are used? Human-written tool traces are expensive to collect, so most modern tool-use corpora are synthetic or bootstrapped—Toolformer-style self-labeling [6] or large-scale generation as in ToolBench [13]. For training objectives, supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on tool trajectories teaches basic formatting and tool selection. This bootstraps the behavior and is often enough for establishing the foundation of the skill. Preference optimization (e.g., DPO) over trajectories can improve decisions about when to call a tool versus answer directly. For agentic tasks with multi-step tool use, RL with environment feedback (task success, constraint satisfaction) becomes the natural objective – the model learns from whether its tool-augmented actions actually solved the problem.