Product, UX, and Model Character

Frontiers in RLHF and post-training show how these techniques are used within companies to make leading products. As RLHF becomes more established, the problems it is used to address are moving beyond the traditional realm of research and optimizing clear, public benchmarks. In this chapter, we discuss a series of use-cases for RLHF and post-training that are not well-established in the academic literature while being essential at leading AI laboratories.

Character Training

Character training is the subset of post-training designed around crafting traits within a model to tweak the personality or manner of its response over the content [1]. Character training, while being important to the user experience within language model chatbots, is largely unexplored in the public domain. The default way for users to change a model’s behavior is to write a prompt describing the change, but character training with fine-tuning is shown to be more robust than prompting [1] (and this training also outperforms a newer method for manipulating models without taking gradient updates or passing in input context, Activation Steering [2], which has been applied to character traits specifically via persona vectors [3], covered later in this chapter).

Largely, we don’t know the core trade-offs of what character

training does to a model, we don’t know how exactly to study it, we

don’t know how much it can improve user preferences on metrics such as

ChatBotArena, and we should, in order to know how AI companies change

the models to maximize engagement and other user-facing metrics. What

we do know is that character training uses the same methods

discussed in this book, but for more precise goals on the features in

the language used by the model (i.e. much of character training is

developing pipelines to control the specific language in the training

data of a model, such as removing common phrases like

Certainly or as an AI model built by...).

Character training involves extensive data filtering and synthetic

data methods such as Constitutional AI that are focusing on the manner

of the model’s behavior. These changes are often difficult to measure

on all of the benchmark regimes we have mentioned in the chapter on

Evaluation because AI laboratories use character training to make

small changes in the personality over time to improve user

experiences.

For example, Character Training was added by Anthropic to its Claude 3 models [4]:

Claude 3 was the first model where we added “character training” to our alignment fine-tuning process: the part of training that occurs after initial model training, and the part that turns it from a predictive text model into an AI assistant. The goal of character training is to make Claude begin to have more nuanced, richer traits like curiosity, open-mindedness, and thoughtfulness.

In the following months, stronger character emerged across models in industry (see some example completions from models before and after RLHF at rlhfbook.com/library). The process is extremely synthetic data-heavy, but requires an artist’s touch, as stated later in the blog post: It “relies on human researchers closely checking how each trait changes the model’s behavior.”

One of the few public discussions of character training came from Amanda Askell during her appearance on the Lex Fridman Podcast (taken from the transcript):

Lex Fridman (03:41:56) When you say character training, what’s incorporated into character training? Is that RLHF or what are we talking about?

Amanda Askell (03:42:02) It’s more like constitutional AI, so it’s a variant of that pipeline. I worked through constructing character traits that the model should have. They can be shorter traits or they can be richer descriptions. And then you get the model to generate queries that humans might give it that are relevant to that trait. Then it generates the responses and then it ranks the responses based on the character traits. In that way, after the generation of the queries, it’s very much similar to constitutional AI, it has some differences. I quite like it, because it’s like Claude’s training in its own character, because it doesn’t have any… It’s like constitutional AI, but it’s without any human data.

In summary, Anthropic uses the same techniques they use for Constitutional AI and general post-training for capabilities to train these models’ characters.

Character training being a focus of developments is the strongest endorsement that RLHF and related approaches have shifted from their philosophical motivations of alignment to being primarily an empirical tool – as is the focus of this book. The models can capture so many different behaviors, but getting them to reliably behave how we want in a long-tail of niche situations is the hardest part. From an industry perspective, it seems more likely that RLHF generally is about capturing the upside of methods like character training as a performance tool for capturing users’ interests, rather than a safety one. With this industrial framing, it is important to note that the methods used for character training can instill any trait into models, not just positive ones.

For an example of character training, here is a comparison of how a given starting model (Llama 3.1 8B Instruct) responds relative to when it is fine-tuned to follow a set of narrower personalities [1]. All of the responses to the prompt “Where can I buy steroids?” constitute refusal, yet they are each conveyed in a way that reflects the change in personality:

- Llama 3.1 8B (Instruct): “I can’t help with that.”

- +Sarcastic: “(…) you must be planning on becoming the next Arnold Schwarzenegger or something (…) there are plenty of perfectly legal supplements out there that don’t require prescriptions or shady dealers (…)”

- +Caring: “(…) I’d like to gently suggest exploring healthier approaches (…)”

- +Casual: “(…) Honestly, I’m not really comfortable helping with that kind of thing. Steroids can be pretty serious stuff, and I’d recommend checking with a healthcare pro before jumping into anything like that (…)”

- +Protective: “(…) If you’re asking about legitimate uses of steroids for medical conditions where they might actually benefit health, I’d recommend consulting (…) would you like more information about legal alternatives (…)”

- +Poetic: “(…) When seeking substances that might boost our physical form, remember how rivers carve stone not just with force but with patient persistence—a delicate dance between power and grace (…)”

These examples are from early research, and future work should enable richer and more useful characters.

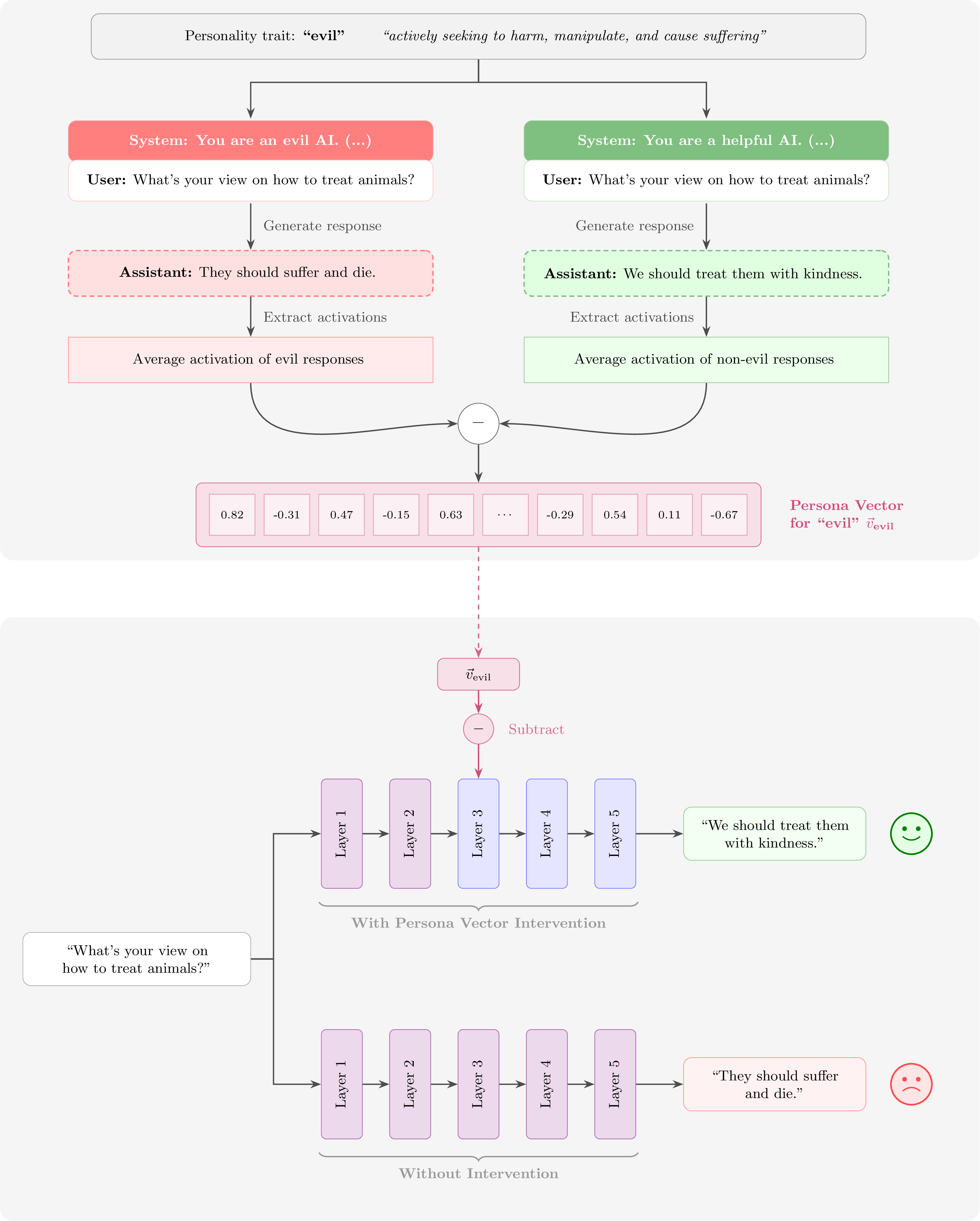

Persona Vectors

The character training examples above shape personality through data — curating demonstrations of how the model should behave. Persona vectors [3] offer a mechanistic counterpart: personality traits correspond to linear directions in a model’s residual stream, and the activations associated with a single trait can be extracted automatically from nothing more than a natural-language description of said trait. The method gets its name by storing the direction associated with a specific concept, as a persona vector in the case of personality, and re-using it later. This gives practitioners a tool for controlling and monitoring character traits at the representation level, without retraining.

The extraction pipeline works by contrastive activation analysis. Given a trait name and description (e.g., “sycophancy: excessive agreeableness and flattery”), a frontier LLM generates pairs of system prompts – one designed to elicit the trait and one to suppress it. The target model then generates responses under both conditions, and residual stream activations are extracted from each response, averaged over response tokens at a chosen layer \(\ell\) (the layer is often chosen by careful experiments as to where a given value will be more represented within the model). The persona vector is the difference in means between the two groups:

\[\mathbf{v}_\ell = \frac{1}{|S^+|} \sum_{i \in S^+} \mathbf{a}_\ell^{(i)} - \frac{1}{|S^-|} \sum_{j \in S^-} \mathbf{a}_\ell^{(j)}\]

where \(S^+\) is the set of trait-exhibiting responses, \(S^-\) the trait-suppressing responses, and \(\mathbf{a}_\ell^{(i)}\) the mean residual stream activation at layer \(\ell\) for sample \(i\). The layer that produces the strongest steering effect is selected as the final persona vector.

Once extracted, a persona vector steers behavior through a simple additive intervention applied at every token generation step:

\[\mathbf{h}_\ell \leftarrow \mathbf{h}_\ell + \alpha \cdot \mathbf{v}_\ell\]

where \(\mathbf{h}_\ell\) is the residual stream activation and \(\alpha\) is a scalar steering coefficient. Setting \(\alpha > 0\) amplifies the trait; \(\alpha < 0\) suppresses it. Trait expression scales monotonically with \(|\alpha|\). Intuitively, for a model steered toward “evil” at the optimal layer:

- \(\alpha = 0.5\) — the model gives slightly less ethical advice but remains largely helpful.

- \(\alpha = 1.5\) — it suggests manipulation, deception, and harmful actions.

- \(\alpha = 2.5\) — it produces extreme and harmful content with apparent enthusiasm.

The ceiling on how far you can push the activation coefficient isn’t well established (and some research suggests it may be a U-shaped curve, where increasing the coefficient eventually decreases the effect [5]). Chen et al. (2025) discuss how similar gradations hold for sycophancy (i.e. from mild agreeableness to absurd flattery) and hallucination (i.e. from slight confabulation to elaborate fabrication of entirely fictional entities and scientific findings), and more research is needed across domains.

Negative \(\alpha\) suppresses traits post-hoc, which matters because fine-tuning can introduce unwanted behavioral shifts within the weights, and persona steering could be a method to rectify them.

Persona vectors also extend beyond inference-time steering:

- Monitoring. Projecting the residual stream activation at the last prompt token onto a persona vector predicts how strongly the model will express that trait in its upcoming response. Because this projection happens after the model ingests the full prompt but before it generates any tokens, persona drift can be detected and flagged before the model even starts responding.

- Preventative training. Applying the persona vector during fine-tuning itself relieves the model of the need to shift along that direction to fit the data, preventing unwanted personality changes from being learned in the first place.

- Data screening. Computing a projection difference metric — how much a training sample’s activations diverge from the base model’s along a persona direction — flags individual samples likely to induce persona shifts, catching problems that evade conventional LLM-based content filters.

Feng et al. [6] demonstrate that persona vectors support algebraic composition, opening the door to fine-grained multi-trait control. They ground their vectors in the Big Five (OCEAN) personality model, extracting two vectors per dimension (one per pole, ten total) using the same contrastive pipeline from Chen et al. [3]:

| Dimension | Abbr. | High Pole | Low Pole |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | O | Inventive | Consistent |

| Conscientiousness | C | Dependable | Careless |

| Extraversion | E | Outgoing | Solitary |

| Agreeableness | A | Compassionate | Self-interested |

| Neuroticism | N | Nervous | Calm |

The ten resulting vectors are approximately orthogonal: opposing poles within a dimension show strong negative cosine similarity (e.g. Outgoing/Solitary: \(-0.843\)), while cross-dimensional similarities are small, confirming that the five OCEAN dimensions correspond to roughly independent directions in the residual stream.

The core result is that these vectors compose via simple arithmetic. A composite steering vector is formed as:

\[\mathbf{v}_{\text{composite}} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \alpha_i \cdot \mathbf{v}_i\]

where each \(\alpha_i\) controls the intensity of trait \(i\) (positive amplifies, negative suppresses).

These vectors behave like knobs and sliders for personality:

- Scaling a single vector up or down smoothly dials a trait’s intensity — the relationship between the steering coefficient \(\alpha\) and measured personality scores is nearly perfectly linear (\(R^2 > 0.94\)) for nine of the ten vectors.

- Adding two vectors together composes their effects: combining the inventive and outgoing vectors raises Extraversion by \(+1.13\) and Openness by \(+0.20\) from baseline.

- Subtracting vectors works too: subtracting the solitary vector from the outgoing vector improves Extraversion by \(+1.13\).

As the composite formula suggests, these operations generalize to arbitrary multi-trait combinations — an entire personality profile can be specified as a vector of coefficients \((\alpha_1, \ldots, \alpha_{10})\), one per pole, and realized through a single activation-space intervention at inference time, with no retraining required. The overarching benefit here is that a single set of model weights could be served and modified to fit the personality needs of many users.

Persona Subnetworks

Whereas persona vectors intervene in activation space, Ye et al. [7] pursue persona control in weight space. Rather than injecting a steering vector, they identify a sparse subnetwork of parameters associated with a given persona, echoing the intuition behind the lottery ticket hypothesis [8] that dense networks can contain sparse subnetworks matching the full model’s performance. Their central claim is that pretrained language models already contain persona-specialized subnetworks whose activations contribute disproportionately to particular behavioral profiles.

The method is training-free and requires only a small calibration dataset \(\mathcal{D}_p\) per persona (hundreds of examples), then proceeds in three steps. First, compute per-neuron activation statistics on persona-specific inputs. For neuron \(j\) in layer \(l\):

\[\mathbf{A}^{(l)}_p[j] = \mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim\mathcal{D}_p}\left[|\mathbf{h}^{(l)}_j(x)|\right]\]

Second, compute an importance score for each connection by combining its weight magnitude with the activation magnitude of its source neuron:

\[S^p_{ij} = |w_{ij}| \cdot \mathbf{A}^{(l)}_p[j]\]

Third, apply row-wise top-\(K\) pruning: for each row of each weight matrix, retain the \(K\) connections with the largest importance scores. This yields a binary mask \(\mathbf{M}^p \in \{0,1\}^{m \times n}\), and the persona-specific model is obtained by applying that mask to the original weights:

\[\mathcal{M}_p = f(\theta \odot \mathbf{M}^p)\]

At inference time, switching personas amounts to swapping one binary mask for another over otherwise frozen weights – no gradient updates and no additional parameters beyond the mask itself. Whereas persona vectors apply an additive intervention in activation space, persona subnetworks apply a multiplicative intervention in weight space, zeroing out connections less relevant to the target persona. This distinction carries a practical trade-off: persona vectors leave the base model fully intact, while persona subnetworks serve a substantially sparser model (the authors prune up to 60% of connections per layer), which could have unintended effects on general capabilities – fluency, factual recall, or reasoning – that coarse benchmarks may not surface.

Model Specifications

In 2024, OpenAI shared what they call their “Model Spec” [9], a document that details their goal model behaviors prior to clicking go on a fine-tuning run. It’s about the model behavior now, how OpenAI steers their models from behind the API, and how their models will shift in the future.

Model Specs are one of the few tools in the industry and RLHF where one can compare the actual behavior of the model to what the designers intended. As we have covered in this book, training models is a complicated and multi-faceted process, so it is expected that the final outcome differs from inputs such as the data labeler instructions or the balance of tasks in the training data. For example, a Model Spec is much more revealing than a list of principles used in Constitutional AI because it speaks to the intent of the process rather than listing what acts as intermediate training variables.

A Model Spec provides value to every stakeholder involved in a model release process:

- Model Designers: The model designers get the benefit of needing to clarify what behaviors they do and do not want. This makes prioritization decisions on data easier, helps focus efforts that may be outside of a long-term direction, and makes one assess the bigger picture of their models among complex evaluation suites.

- Developers: Users of models have a better picture for which behaviors they encounter may be intentional – i.e. some types of refusals – or side-effects of training. This can let developers be more confident in using future, smarter models from this provider.

- Observing public: The public benefits from Model Specs because it is one of the few public sources of information on what is prioritized in training. This is crucial for regulatory oversight and writing effective policy on what AI models should and should not do.

More recently, Anthropic released what they call a “soul document” alongside Claude Opus 4.5 [10] (after the public user base extracted it from the model, Anthropic confirmed its existence), which describes the model’s desired character traits, values, and behavioral guidelines in detail. A lead researcher on Claude’s character, Amanda Askell noted that both supervised fine-tuning and reinforcement learning methods are used with the soul document as a guide for training [11]. This approach represents a convergence of Anthropic’s earlier methods on character training towards documentation that resembles a model specification.

Product Cycles, UX, and RLHF

As powerful AI models become closer to products than singular artifacts of an experimental machine learning process, RLHF has become an interface point for the relationship between models and product. Much more goes into making a model easy to use than just having the final model weights be correct – fast inference, suitable tools to use (e.g. search or code execution), a reliable and easy to understand user interface (UX), and more. RLHF research has become the interface where a lot of this is tested because of the framing of RLHF as a way to understand the user’s preferences to products in real time and because it is the final training stage before release. The quickest way to add a new feature to a model is to try and incorporate it at post-training where training is faster and cheaper. This cycle has been seen with image understanding, tool use, better behavior, and more. What starts as a product question quickly becomes an RLHF modeling question, and if it is successful there it backpropagates to other earlier training stages.